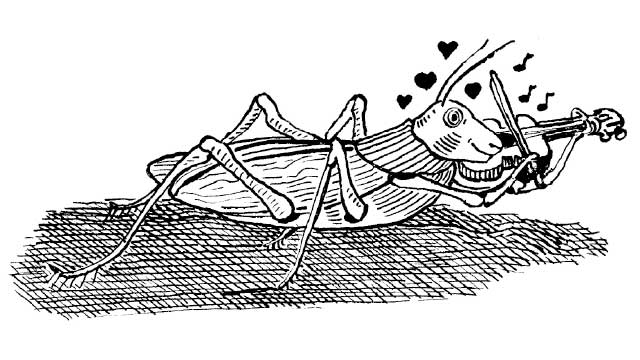

ANDRZEJ KRAUZEIn the wee hours of the morning earlier this year, my restless wife lay in bed and groaned: “That cricket must die. Now.” The amorous insect, perched very near our bedroom window, had been steadily chirping since sundown the previous evening. While well and good for his chances of securing a mate, the animal’s volubility was endangering the harmony of my own marital union.

ANDRZEJ KRAUZEIn the wee hours of the morning earlier this year, my restless wife lay in bed and groaned: “That cricket must die. Now.” The amorous insect, perched very near our bedroom window, had been steadily chirping since sundown the previous evening. While well and good for his chances of securing a mate, the animal’s volubility was endangering the harmony of my own marital union.

Nevertheless, we let him sing. And as I listened to the six-legged crooner, I was reminded that music is in the ear of the beholder. Or more precisely, in the beholder’s brain.

Thinkers have waxed poetic about the musical qualities of birdsong for centuries. “And hark! the Nightingale begins its song, / ‘Most musical, most melancholy’ bird!” wrote Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1798. A few decades later, Percy Bysshe Shelley celebrated the skylark: “Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert,...

Even Charles Darwin was guilty of romanticizing music in nature. “Musical notes and rhythm were first acquired by the male or female progenitors of mankind for the sake of charming the opposite sex,” he wrote in The Descent of Man.

But are the refrains of nature—from melodious birdsong to the emergent rhythmicity of insect calls to Darwin’s hypothesized mate-charming proto-serenade—actually “music”? Or is it we humans who bring that label and all its cultural baggage to the party?

Science tells us that our brains are expert pattern generators. So adept is the human brain at creating order out of disorder that it can find religious figures in burnt toast and dragons in a cloudy sky. Perhaps, then, it is also finding music in the sounds of nature.

As is the hallmark of interesting lines of scientific inquiry, research into the biology of music has precipitated more questions than answers. I can report that whether nonhuman animals produce “music” is far from settled. Some researchers we interviewed for this special issue on music suggested parallels between a singing male bird and a rock star wailing away before adoring fans. Others rejected the idea that human music and the vocalizations of birds or bats or whales have much to do with each other at all. They framed the vocalizations and instrumentations of nonhuman animals as dispassionate, almost automatic utterances, honed by evolution to efficiently communicate specific messages to their intended audiences.

While I know well the dangers of suggesting that specific behaviors are uniquely human, I also realize that some of our eccentricities do set us apart from the rest of the animal kingdom; wearing pants and watching TV come to mind. So are we merely one player in a vast animal orchestra? Or are we alone in producing and listening to music for sheer enjoyment? I tend to agree with the latter, but remain open, as ever, to evidence-based shifts in my thinking.

Of course, all of this conceptual wrangling means very little to our friend the cricket. Although he didn’t return to our window for an encore after so annoying my better half, I’m positive his own biology compelled him to chirp the night away elsewhere, blissfully unquestioning of his innate drive to do so.

This is not to say that I begrudge Coleridge or Shelley or Darwin the pleasure of finding beauty or charm in the chorusing of birds or the thrumming rhythms of water and wind. I delight in some of the very same patterns, not to mention the musicality of an overloaded washing machine or a bustling city street. But to say that nature is inherently humming with music is to ignore the very real contribution of our own cognitive abilities to the composition of this symphony.

Bob Grant

Senior Editor

Special Issue Coordinator

Interested in reading more?