FLICKR, AIR NATIONAL GUARD, SSGT DANIEL J. MARTINEZAt dusk on Thursday (September 14), U.S. Air Force Reserve cargo planes took to the skies over Harris County, Texas, to spray about 600,000 acres around Houston with a potent mosquito-killing insecticide, complementing similar efforts across other counties in Texas affected by Tropical Storm Harvey. Widespread and prolonged flooding in the region has multiplied the insects’ habitats.

FLICKR, AIR NATIONAL GUARD, SSGT DANIEL J. MARTINEZAt dusk on Thursday (September 14), U.S. Air Force Reserve cargo planes took to the skies over Harris County, Texas, to spray about 600,000 acres around Houston with a potent mosquito-killing insecticide, complementing similar efforts across other counties in Texas affected by Tropical Storm Harvey. Widespread and prolonged flooding in the region has multiplied the insects’ habitats.

“We are hopeful that the spraying will help prevent an increase in mosquito-borne disease,” Chris Van Deusen, director of media relations for the Texas Department of State Health Services, tells The Scientist.

Under normal circumstances, Harris County Public Health deploys trucks that spray insecticide in an area only if a mosquito trapped there carries disease. “But there is nothing normal about Harvey because there’s water everywhere,” says entomologist Mustapha Debboun, the director of mosquito and vector control for Harris County Public Health....

After flooding, an upsurge in the number of mosquitoes is common because eggs laid during previous floods hatch and develop. Van Deusen explains that most of these mosquitoes are a nuisance, but unlikely to cause disease.

The species that carry viruses have slightly different life cycles, but their numbers are also likely to rise as excess water expands their favorite hatching grounds. Aedes aegyti, the primary mosquito that transmits Zika virus, favors water-filled containers, such as empty flowerpots or old tires. Mosquitoes of the genus Culex, the vectors for West Nile virus, prefer to lay their eggs in ditches or storm sewers.

Typically, officials monitor population levels of these and other species using a network of traps throughout Harris County, as well as a measurement of how many mosquitoes land on a person in one minute, called the landing-rate count. Debboun’s team has used a similar landing-rate surveillance method since the storm and seen a wide variation in numbers. In places with lots of water and vegetation, counts have been more than 100 per minute, double the levels that would normally be considered high.

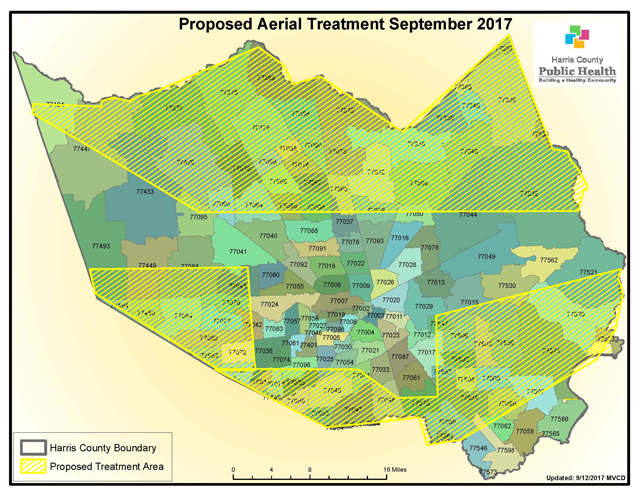

MOSQUITO & VECTOR CONTROL DIVISION, HARRIS COUNTY PUBLIC HEALTH

MOSQUITO & VECTOR CONTROL DIVISION, HARRIS COUNTY PUBLIC HEALTH

Every night since Labor Day, Debboun has sent trucks to spray insecticide from dusk until 5:30 A.M. in the accessible areas with the highest mosquito counts. “Because of the flood there’s going to be more water. There are going to be more mosquitoes, and so we have to do the best we can,” says Debboun.

In Harris County, 2017 has so far seen five human cases of Zika virus—likely acquired during travel to regions with local transmission—and two human cases of West Nile virus. It remains to be seen whether Texas will have more human cases of West Nile, Zika, or any other mosquito-borne viruses after Harvey.

Van Deusen explains that any increase could be delayed. “That’s one of the things that we’re trying to combat,” he says. “It varies from event to event whether there is an increase in mosquito-borne disease after a flood like this.”

Interested in reading more?