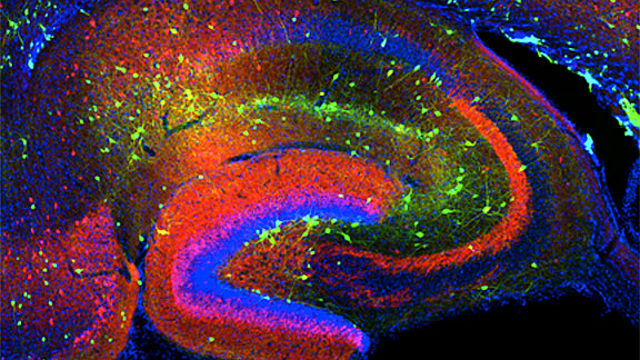

Section of a mouse hippocampusFLICKR, NICHDZika virus infection leads to epigenetic modifications of both the virus and human RNA molecules, leading to changes in viral replication and the human immune response, according to a study of cell cultures published last week (October 20) in Cell Host & Microbe.

Section of a mouse hippocampusFLICKR, NICHDZika virus infection leads to epigenetic modifications of both the virus and human RNA molecules, leading to changes in viral replication and the human immune response, according to a study of cell cultures published last week (October 20) in Cell Host & Microbe.

“I’m excited about this study because it teaches us something new about the human immune system,” study coauthor Tariq Rana of the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine said in a press release. “But these findings are also something researchers should keep in mind as they are designing new Zika virus vaccines and treatments that target the viral genome—some approaches won’t work unless they take methylation into account.”

Specifically, Rana and colleagues found that methylation of viral RNA serves as “a beacon for human enzymes that come along and destabilize it,” according to the press release,...

Meanwhile, researchers studying animal models of Zika infection have found that the virus may induce programmed cell death in the brains of newborn mice. “In early postnatal Zika-infected models some brain areas and cell types showed particularly large increases in apoptosis that we did not observe in older animals,” study coauthor Hyeryun Choe of the Scripps Research Institute in Florida said in a press release. Choe and colleagues’ findings, published October 7 in Nature Scientific Reports, suggest that Zika can attack post-mitotic but still-growing neurons, in addition to neural progenitor cells.

Researchers are also continuing to glean insights into Zika biology from people who have been infected with the virus. Last week (October 18), a team in Texas found that a non-pregnant 26-year-old American woman who was infected with Zika virus during a trip to Honduras harbored the virus in her vaginal secretions for two weeks after the onset of infection symptoms, and in her blood for nearly three months. “This confirms our suspicions concerning risk of sexual transmission from females to males, with our study finding this risk of infectivity to be approximately two weeks after onset of symptoms,” Kristy Murray of Baylor College of Medicine said in a press release. The team published its findings in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

More information on the virus can’t come fast enough, as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) earlier this month announced that Zika is now spreading in a small area of Miami. As a result of this local spread, the agency has issued more-robust travel recommendations for pregnant women and has reiterated its recommendation that people in affected areas take measures to prevent Zika exposure.

Considering the threat in Florida and elsewhere in the U.S., the CDC last week (October 19) announced some $70 million in funding for efforts to stop the spread of Zika virus, including surveillance programs and improved mosquito control, and to monitor Zika-exposed pregnant women and their infants. The deadline for applications is November 20.

Interested in reading more?